A short note on the topic of wood

by Christine Richter (CHARMS)

In July 2022 I went on a short visit to the City of Chiang Mai. Khun Nuchwaree Boonkumkrong was a kind guide through the city and region. We drove, walked, and visited people and places; and Khun Nuch not only introduced me to the city, its many temples and neighborhoods, but also guided us on a sort of mission in the search of wood. Inspired by Edmund de Waal’s “The White Road” (tracing the movements of porcelain) combined with my STS-ish inclination to follow objects and specific materials to untangle networks and infrastructural relations, one of my aims was to learn about wood: its uses in the city, people’s perceptions of the material, its meanings, where it comes from and where it goes, and, eventually even wondering about, what it actually is. While this journey remains a work in progress, this news post is a first, very brief, reflection.

What is wood: vine, branch, or trunk? Near Mae Kampong in the mountains east of Chiang Mai (Photo: Christine Richter, Fraunhofer IMW, July 2022).

The trade of teak wood has played an important role in the history of the region and, as in many places in Southeast-Asia, wood has long been an important construction material. But wood is much more than a trade commodity or construction material for houses and temples. It symbolizes urban progress, retaining the old in the new. We find it in fashionable elements on modern shops and coffee houses, serving young people as background for selfies, and on modern public buildings indicating status.

Coffeeshop on Huay Kaew Road in the modern Nimmanhaemin neighborhood (Photo: Christine Richter, Fraunhofer IMW, July 2022).

At the same time, it represents an essence of the region’s culture and history, and a sustainable way of managing urban housing. Wood, in its various facets, including the light bamboo or the more permanent teak wood, drives the dynamic and complex interactions between the forest, the laws and policies that govern forestry, wood trading, construction, land use and planning, the skills and knowledge of wood craftspeople and the communities of carpenters, who pass on these sets of skills, the architects and cultural advocates, who work with and promote the use of wood in urban construction, the residents of the city, who live in modern or older wooden houses, and to whom the wooden walls of their homes may contain decades of family history. Wood helps to create and maintain a sense of community and belonging in neighborhoods and is associated with memories, a specific atmosphere and smells, but it also constitutes an urban-economic factor, quite literally migrating across the city, with homes being torn down and rebuilt elsewhere, as land prices, land uses and location preferences across generations change.

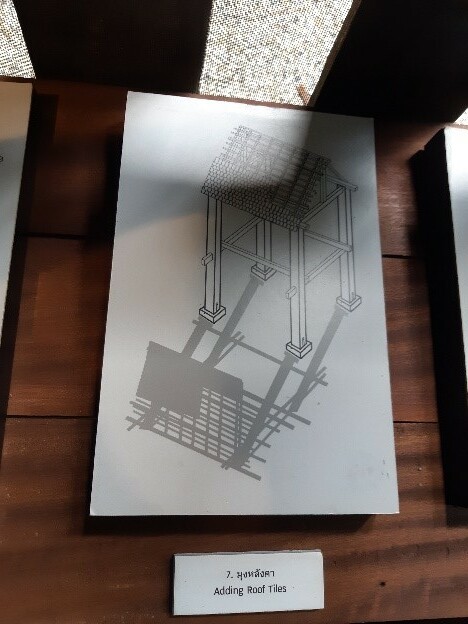

Remembering craftsmanship and methods in vernacular wood construction: Inside the Lanna Traditional House Museum (Chiang Mai University), one of the illustrations depicting various stages and elements of house construction (Photo: Christine Richter, Fraunhofer IMW, July 2022).

As such, talking about wood also opens new ways to understand the varied perceptions of (cultural heritage) preservation in the context of a northern Thai city, because while being a historically important and culturally significant material wood is at the same time associated with notions of impermanence and temporality.

I am about to go for another visit to Chiang Mai in March 2023 to conduct a number of Q-sort interviews to learn about residents’ various views about the preservation of wooden buildings for residential uses. Although Q-sort interviews are highly structured, I am quite sure that – branching out a bit – we will also learn more about the many meanings of wood in the city.